From archive to exhibition – A search for Wilhelm Martin

During my internship at the Mauritshuis in 2018, I was given the seemingly simple assignment to find out more about the former director Wilhelm Martin. No one could have known that this assignment would form the basis for years of research on Martin, yielding not only a master's thesis, but also articles, a book, an exhibition, and eventually PhD research. This certainly would not have been possible without the RKD, where Martin's archive resides and which proved an indispensable resource. Wilhelm Martin was much more versatile and interesting than imagined, and very important to the history of the Mauritshuis, where he oversaw between 1909 and 1947.

Who was Wilhelm Martin?

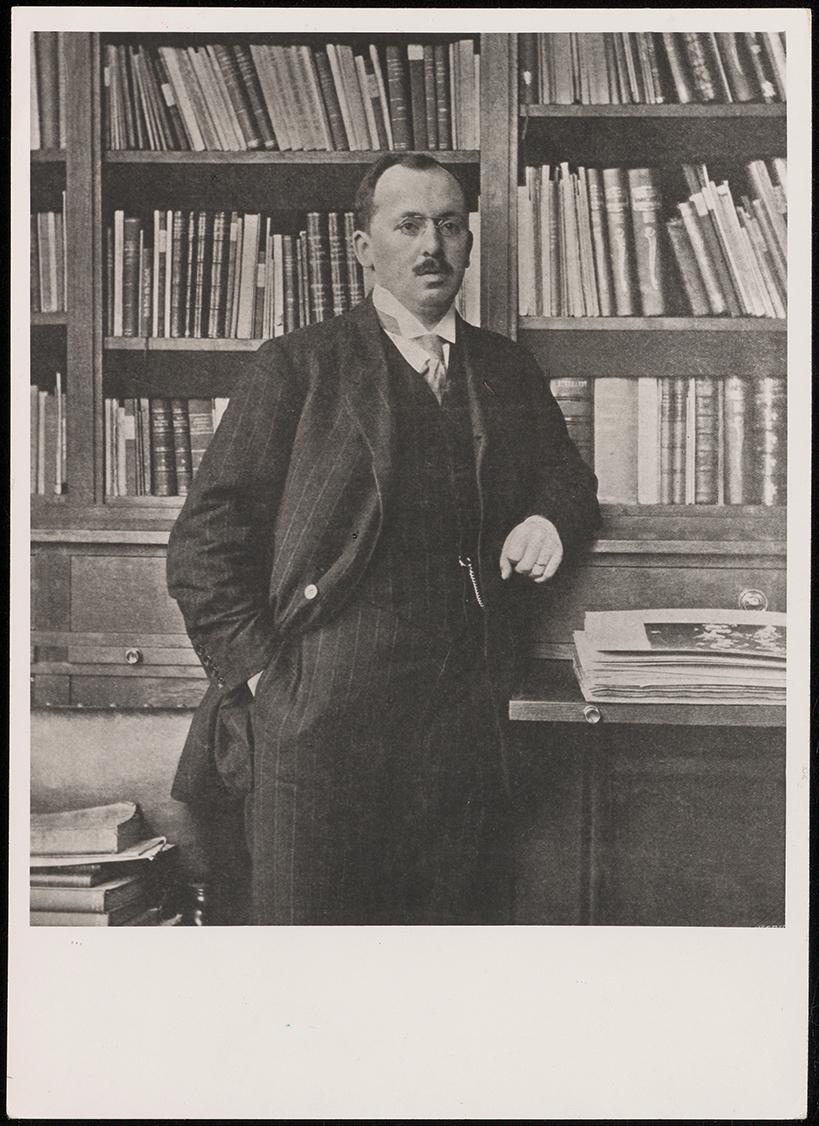

Wilhelm Martin was born in 1876 in Quackenbrück, Germany. His parents were Johann Karl Ludwig Martin (1851-1942), and Anna Christina Maria Fittica (1846-1906). When Wilhelm was a year old, the family moved to the Netherlands because his father was appointed professor of geology at Leiden University. The family settled in Leiden at 55 Breestraat. Martin had two younger sisters and two younger brothers. After attending grammar school, Martin's ambition was to become an artist. Presumably at his father's insistence, he instead started studying literature in Leiden, a study he completed in 1901 with a dissertation on the artist Gerrit Dou.Footnote1 This was the first art historical dissertation published in the Netherlands. That same year, Martin started as deputy director at the Mauritshuis. Thus began a busy period. He published widely, was a member of several organizations and became a private lecturer in art history in 1904. A year after his marriage in 1906 he was appointed extraordinary professor at Leiden University. In 1909 he succeeded Abraham Bredius as director of the Mauritshuis. In 1934, Martin was additionally appointed director of the Rijksmuseum Hendrik Willem Mesdag in The Hague and, shortly thereafter, director of the Print Room at Leiden University. He did not retire until 1953, barely six months before his death in 1954.

Martin preferred to stay out of the spotlight and did not present himself like many of his colleagues, including his flamboyant, quirky predecessor Bredius. Consequently, Martin is rather unknown, even though he made crucial contributions to the field of seventeenth-century art history and to the restoration and conservation of old paintings. From his archive and the descriptions of others, the image arises of a man with diplomatic gifts, able to mediate between different parties and remain cool and composed. He emerges as a meticulous researcher and strategic thinker who does not let events take him by surprise. This attitude served him well throughout his career and enabled him to remain level-headed when in contact with people whose views he did not share.

(Re)discovery of an archive

The first step in my search for Wilhelm Martin, about whom I knew virtually nothing, was the Archive Wilhelm Martin at the RKD. This archive is a valuable source not only for Martin's life, but also for his significance as a researcher of Dutch painting of the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. Martin was always closely associated with the RKD: he knew the founders Cornelis Hofstede de Groot and Frits Lugt well, and the first directors Hans Schneider and Jan Gerrit van Gelder even better. From the start he was involved with the RKD, supporting the establishment of the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie at Korte Vijverberg 7, a stone's throw from ‘his’ Mauritshuis. For instance, he donated many photographs and catalogues of the Mauritshuis to the RKD. In 1949, he personally donated a careful selection of research material and huge numbers of reproductions, now embedded in the RKD's image collection.Footnote2 After his death, the Martin archive was further expanded by donations from his widow, children and grandchildren. These donations, some of which were added only a few years ago, were less carefully selected and contain a lot of personal correspondence and photographs. This makes the Martin archive, although certainly not complete, invaluable for data on his person and his research. Despite this wealth of information, very little research on Martin has been done so far and there is hardly any secondary literature on him.Footnote3

The archive was virtually untouched when I started my research. Former RKD-director Rudi Ekkart had looked at it and written about Martin, but it had not been inventoried and many of the newer acquisitions were still in old shoeboxes without any order.Footnote4 Looking at nearly six meters of archive, I faced the great challenge of distilling a picture of a person and a life from an overwhelming heap of letters, clippings, fiches, photographs and notes. It soon became clear that Martin’s activities were too comprehensive to cover in my master's thesis. I could only focus on one sub-area, but the wealth of interesting stories made me want to engage with Martin for a longer period. My research allowed me to organize and inventory the Martin archive, making it easier to find and reference specific records. It also clarifies to researchers what kind of information can be found in the archive.

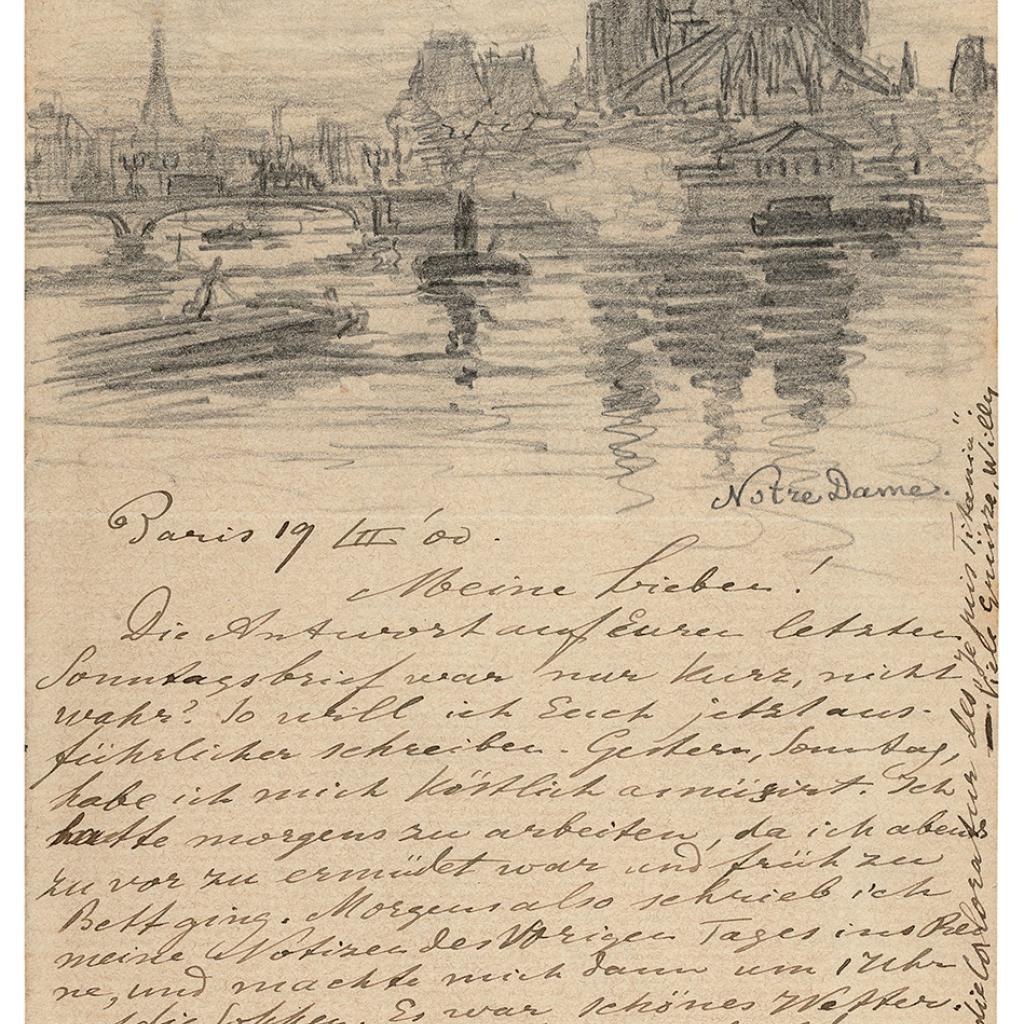

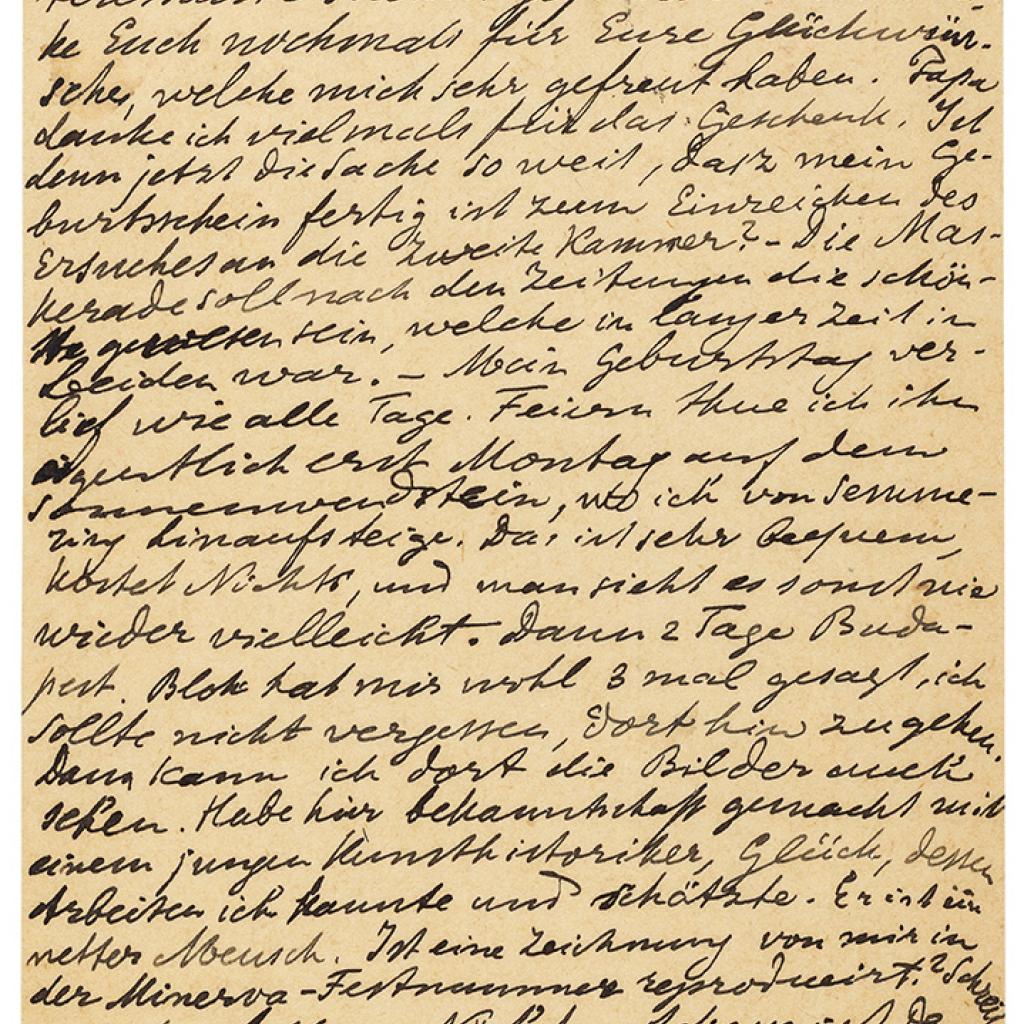

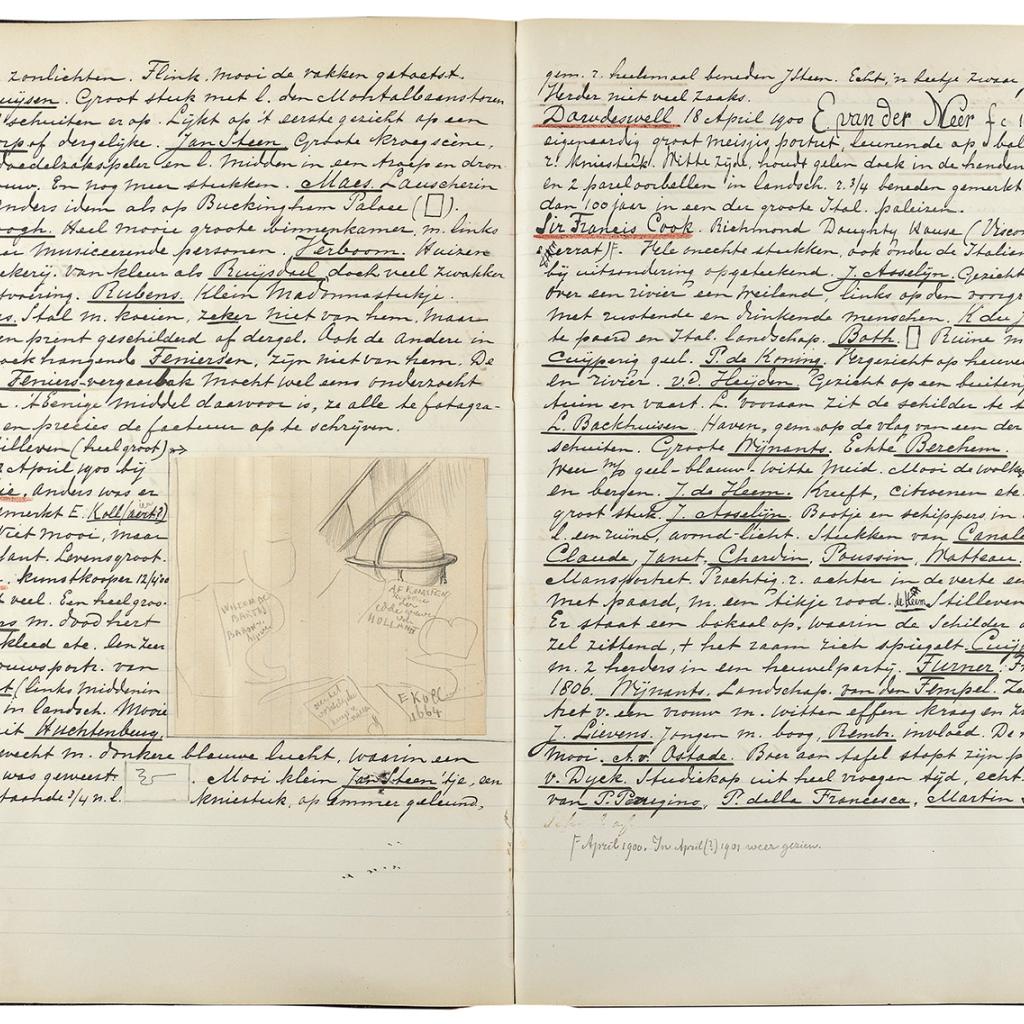

Europe trip

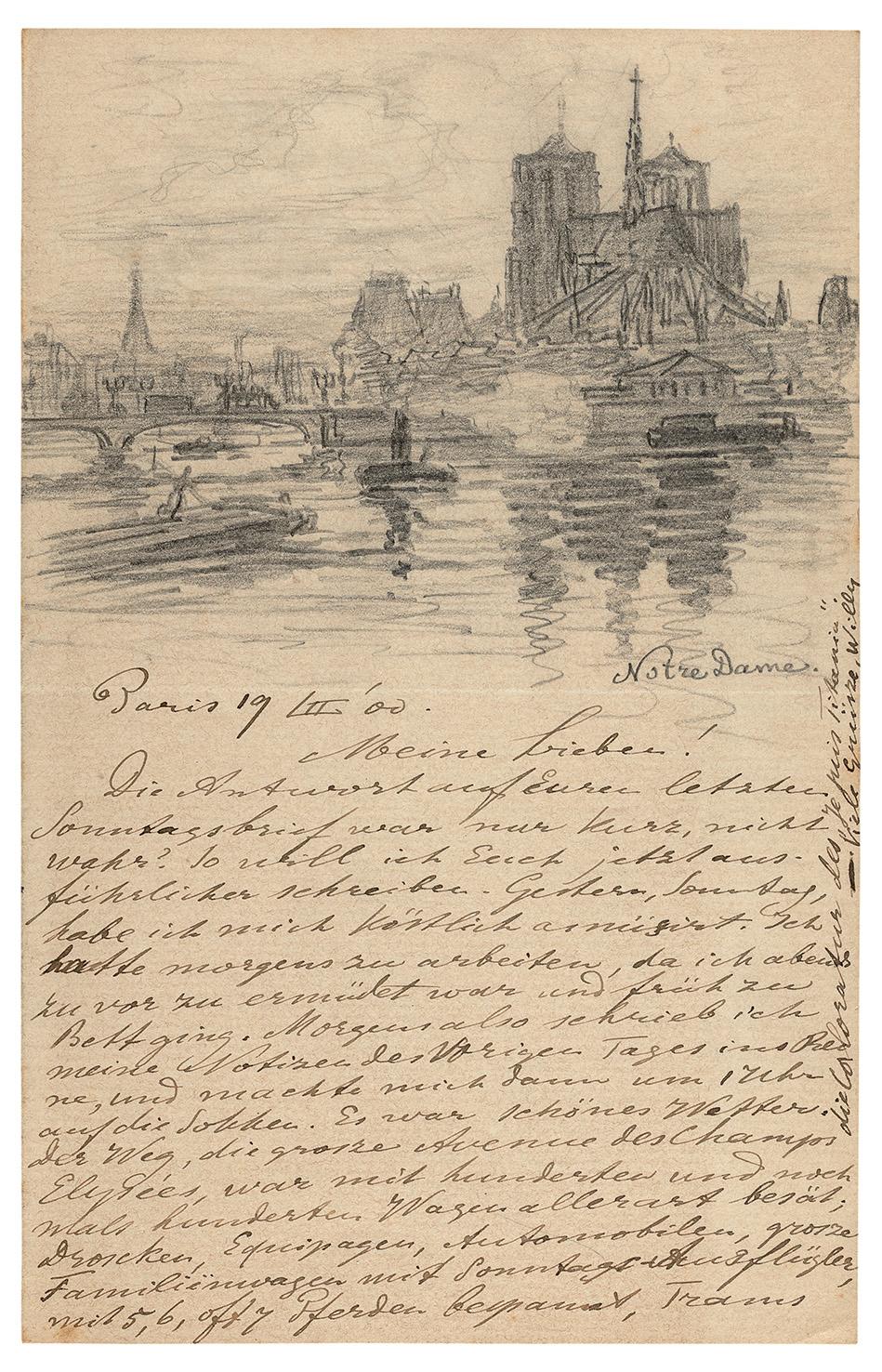

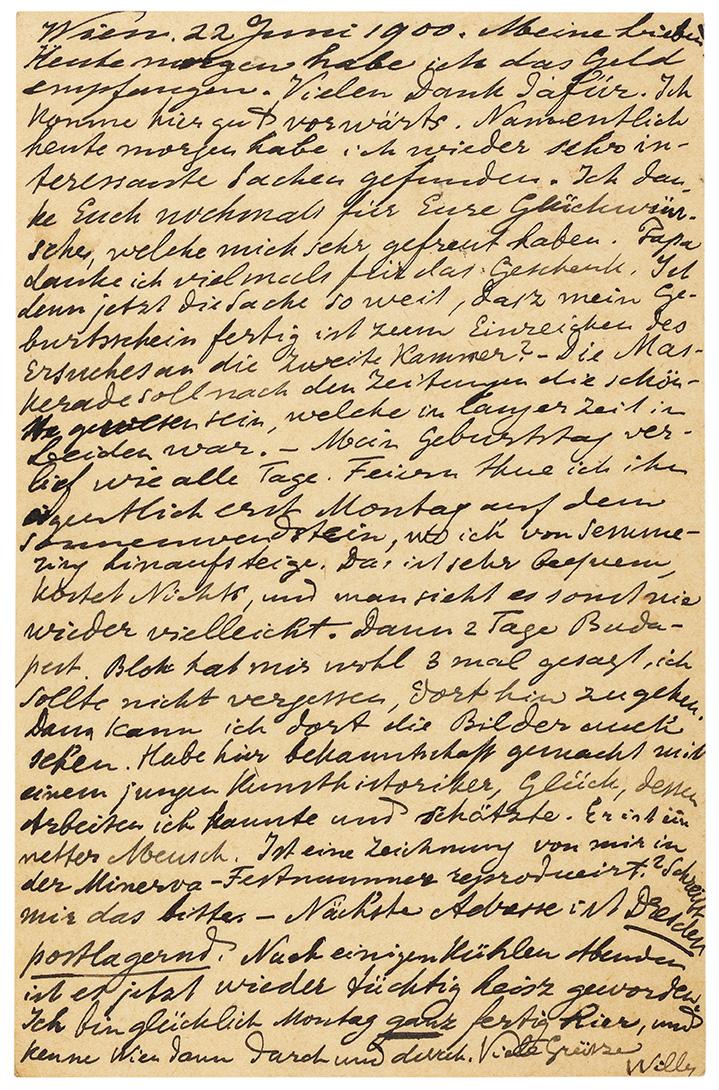

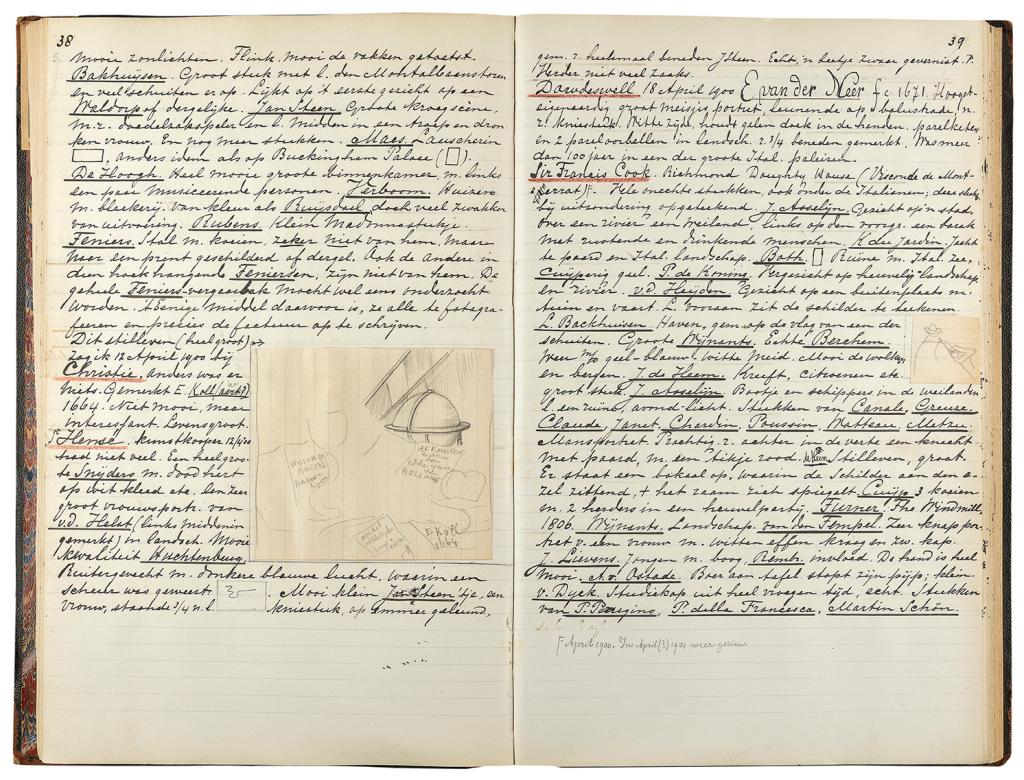

Very interesting, for instance, are the letters Martin sent home during his Europe trip in 1900. He was then working on his thesis on Gerrit Dou under the supervision of Professor Blok and had received a stipend to travel around Europe for several months with the aim of seeing as many of Dou's paintings as possible and consulting foreign archives. This was a great opportunity for the young Martin to make his way in the world of art history and get to know many important experts and collectors. In letters to his parents, he described in detail (in German) what he had experienced on his trip, who he had met and what he had seen. He painted an interesting picture of fin de siècle Europe, but also expanded his art-historical knowledge. In a bulky notebook, he meticulously noted down all the museums and collections and the paintings he had seen. He often noted not only the basic details but also his opinion on attributions and quality, sometimes even including a small sketch of the work.

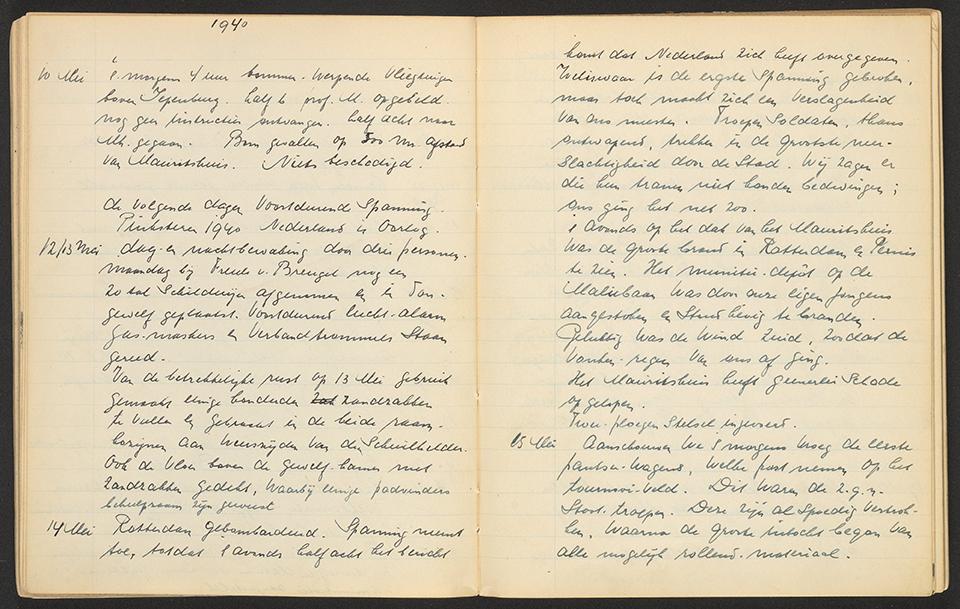

Huis in de storm

In addition to the Martin archive, the Mauritshuis archive was a useful source, especially in conjunction with each other.Footnote5 This includes the period of World War II. Ever since the discovery in 2012 of a small logbook of the “official of administration”, in which Mense de Groot, appointed to this position in 1940, wrote extensively about the wartime, the Mauritshuis had the idea of conducting in-depth research into its own history of that time. When I found documents from the war in Martin's archive, it coincided nicely with the museum's plans. The three-year Mauritshuis research project Mauritshuis in Wartime started in 2021, with research partners RKD and NIOD, and with support from the Mondriaan Fund ‘75 Years of Freedom’ grant scheme. Upon completion of the project, the results were made public through the scholarly publication Huis in de storm – Mauritshuis in oorlogstijd and the exhibition Facing the Storm – A Museum in Wartime in the Mauritshuis (on view until 29 June 2025). I participated in this research and got in touch with Martin's descendants, who supported me and gave access to the family archives. Much of this source material has since been added to the Martin archive at the RKD.

Wartime director

Martin, as a wartime director, played a central role in World War II research. However, he had never intended to remain director for so long. In 1941 he was pensionable and wanted his intended successor J.G. van Gelder to take charge, but this was not allowed by the German occupiers since Van Gelder was married to a woman who was “half-Jewish” according to the Nazi lineage doctrine. For several months, the various officials and museum directors brainstormed in the department about who would qualify, but all the other candidates were either unsuitable or also Jewish. In the end, they had to ask Martin to stay put.Footnote6 Martin, who had devoted almost his entire life to the Mauritshuis, was willing to do so. Looking back, it was perhaps this decision that brought the Mauritshuis – building, collection and staff – safely through the war.

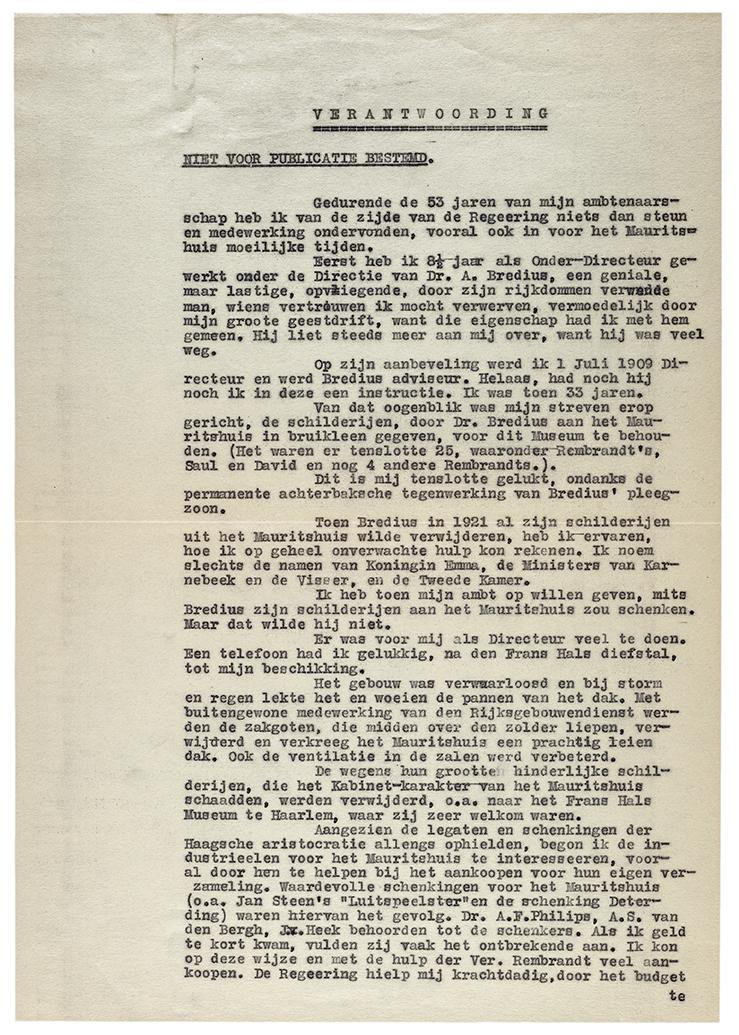

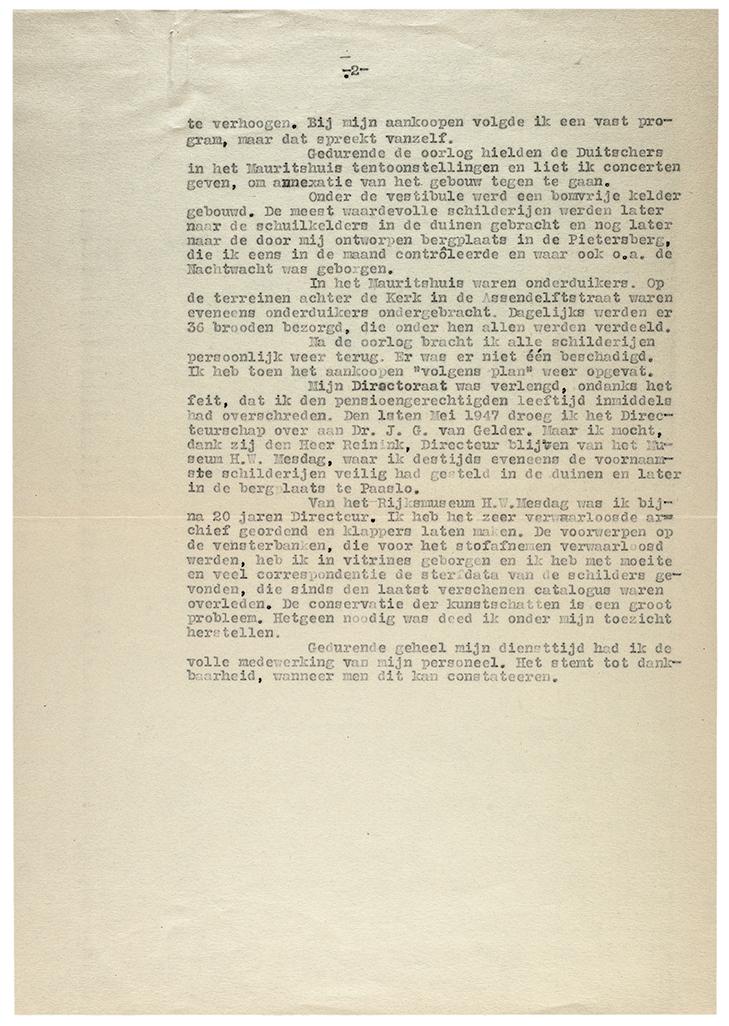

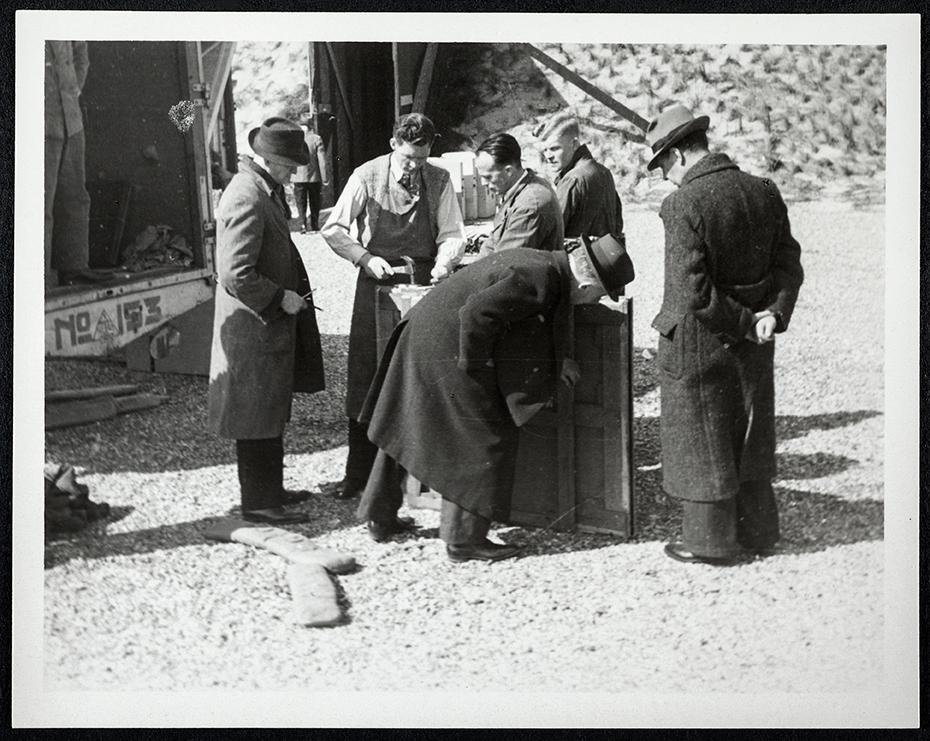

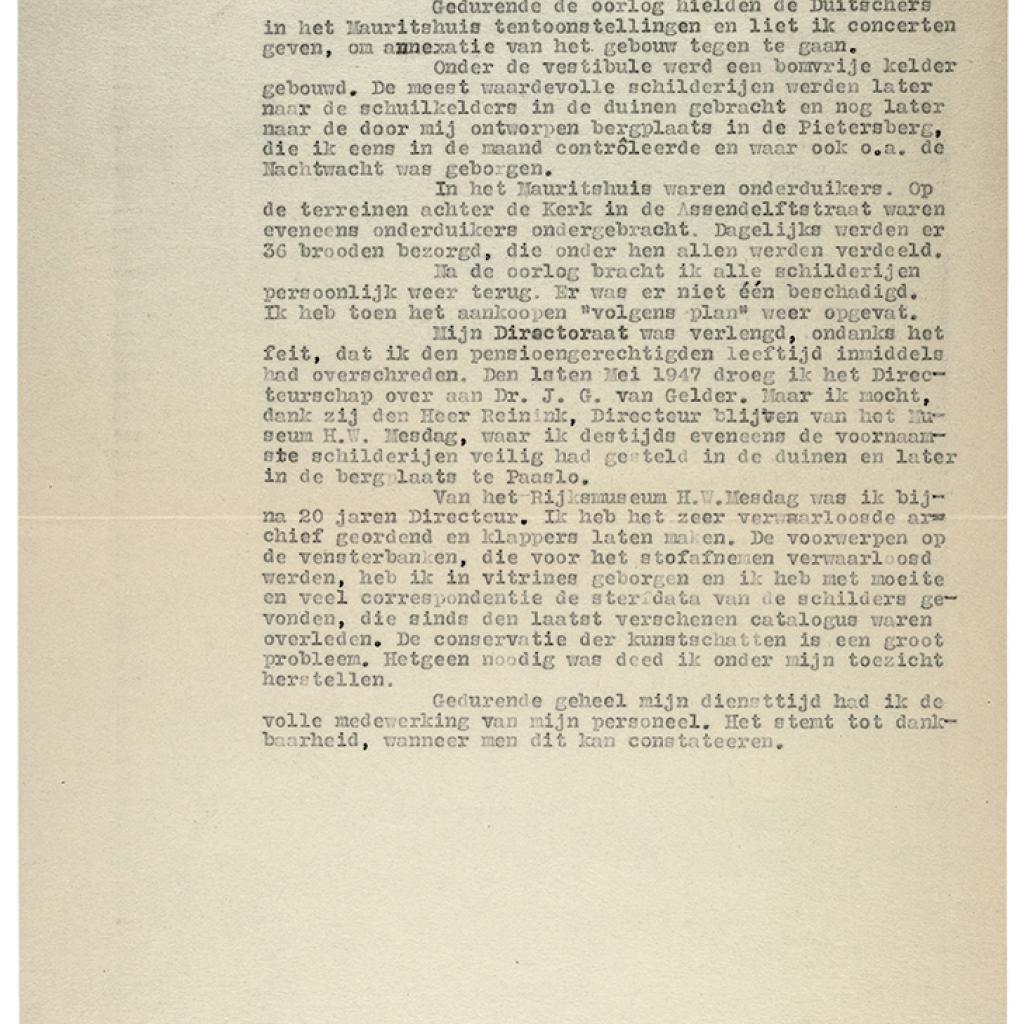

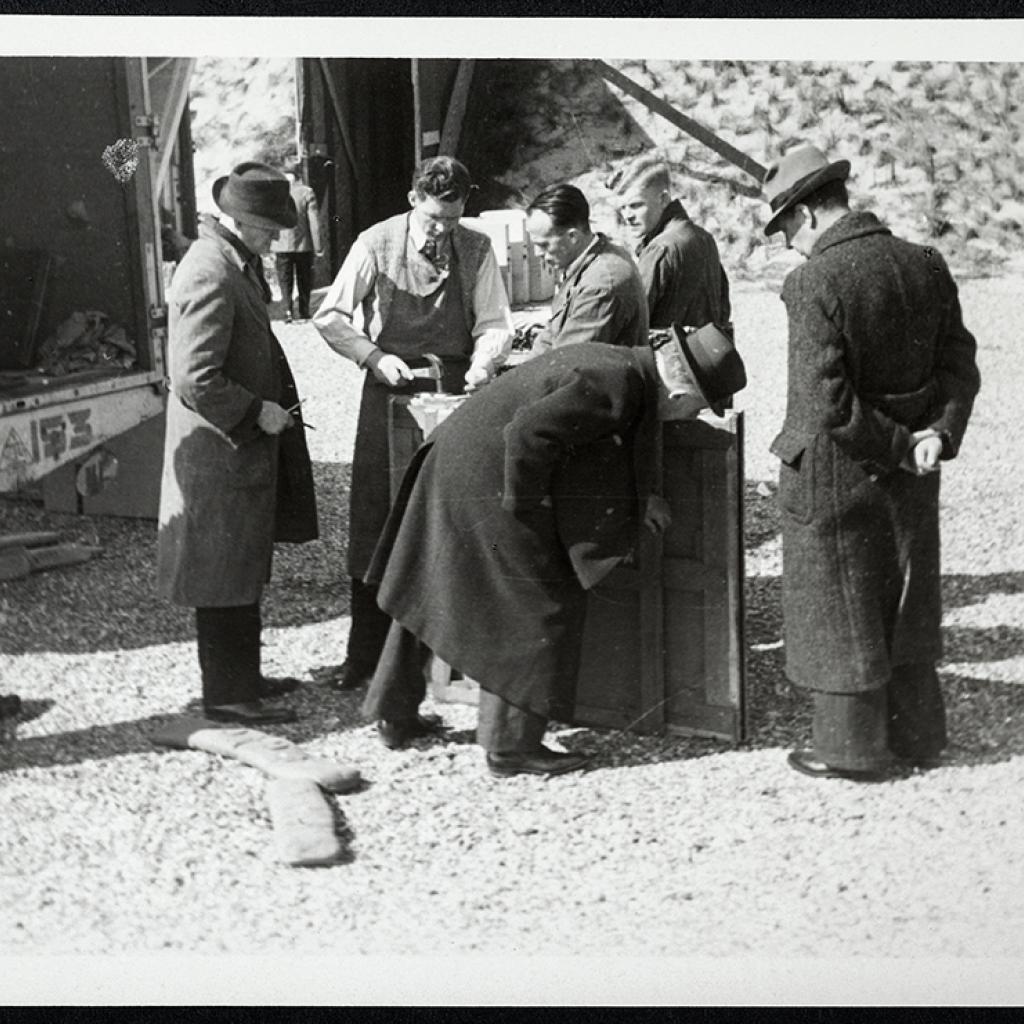

In the Martin archive, I also found a Verantwoording (justification), a document he had sent to the ministry as an attachment to his resignation in 1953. In it, he looks back on nearly fifty years of service as a civil servant. In just ninety-nine words he summarizes the war years, ending with the joyous statement: 'After the war, I personally returned all the paintings. Not a single one was damaged!' It had largely been thanks to Martin's efforts that the collection was protected. Shortly before the war, he had a bombproof vault constructed under the museum, where the most important pieces found shelter. He also managed to protect the building itself and its staff. He had concerts given in the museum to avoid annexation by the occupation force, but also had to accommodate propaganda exhibitions of in the museum. It was a delicate balance between accommodating and resisting, with Martin's diplomatic and calm demeanor coming in handy.

Impact on Dutch art history

It speaks for Martin that, even after years of research, a book, an exhibition and a dissertation (intended completion 2026), there is still much to be told.Footnote7

Many of his art historical research projects, for example on nineteenth-century painting, have hardly been studied. Today, the increasing digitization of archives makes it possible to reconnect various parts of his archive in and also outside the RKD, which can provide additional knowledge. It is already becoming clear that Martin, with his multifaceted interests and research, his many functions and his large network, not only played a central role in the Dutch museum scene, but also had a significant impact on Dutch art history and the development of the profession.

Author

This RKD Story contains elements from Q. Buvelot and F. van Vree (red.), Huis in de storm – Mauritshuis in oorlogstijd, Zwolle 2025. Marie Mundigler and Evelien de Visser are working on an article on Wilhelm Martin and his unfinished catalogue raisonné of the Hague School (1913-1919) planned for Oud Holland (currently under peer review).

- Back to footnote 1 in the text

W. Martin, Het leven en de werken van Gerrit Dou beschouwd in verband met het schildersleven van zijn tijd, thesis Leiden University, 1901.

- Back to footnote 2 in the text

The Hague, RKD – Dutch Institute for Art History, RKD-Archive 1932-1975 (0328), inv.nr. 26 (letter from Martin to H. Gerson, 1 September 1949). Annual report Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie, The Hague 1949, pp. 2-3.

- Back to footnote 3 in the text

There are, however, several studies that discuss Martin sideways, including: F. Grijzenhout and H. van Veen, De Gouden Eeuw in Perspectief. Het beeld van de Nederlandse zeventiende-eeuwse schilderkunst in later tijd, Heerlen 1992; A. Hoogenboom, ‘Kunstgeschiedenis aan de universiteit: Willem Vogelsang (1875-1954) and Wilhelm Martin (1876-1954)’, in P. Hecht, C. Stolwijk and A. Hoogenboom, Kunstgeschiedenis in Nederland, Amsterdam 1998, pp. 25-44; C. Scallen, Rembrandt, Reputation and the practice of connoisseurship, Amsterdam 2004.

- Back to footnote 4 in the text

R. Ekkart, ‘Wilhelm Martin, een kunsthistoricus in de schaduw van zijn tijdgenoten’, RKD Bulletin 2008, p. 16 and R. Ekkart, ‘Wilhelm Martin’, in Biografisch Woordenboek van Nederland. URL: http://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/bwn1880-2000/lemmata/bwn2/martin [12-11-2013]

- Back to footnote 5 in the text

The Mauritshuis archive is handed over to the National Archives (NA 2.14.130).

- Back to footnote 6 in the text

J.G. van Gelder did become acting director of the RKD and was able to become director of the Mauritshuis after the war.

- Back to footnote 7 in the text

M. Mundigler, Wilhelm Martin and the art of restoration in the Netherlands in the early 20th century, master’s thesis University of Amsterdam 2019; Marie Mundigler and Evelien de Visser are working on an article on Wilhelm Martin and his unfinished catalogue raisonné of the Hague School (1913-1919) planned for Oud Holland (currently under peer review).; M. Mundigler, ‘Wilhelm Martin – Directeur in Oorlogstijd’, in Q. Buvelot and F. van Vree (red.), Huis in de storm – Mauritshuis in oorlogstijd, Zwolle 2025, pp. 86-95.